Design research: discovering meaning, innovation types, pitfalls

Design Research: Methods and Perspectives edited by Brenda Laurel

Unlike Do You Matter?, which takes a “just do it!” approach to experience design, Design Research

, is filled with practical techniques and frameworks to help you understand customers, discover latent needs, validate assumptions, and design your customer experience.

With such a large number of tools available, when should they be used? And to what end? The three videos below provide some answers. Darrel Rhea, who wrote the Divergent and Convergent Thinking essay, believes design research contributes directly to innovation and creates value by delivering user experiences which align with people’s values. Don Norman, who has written extensively about industrial design and user experience and wrote the foreword to Laurel’s book Computers as Theatre, concludes that traditional design research can only support incremental innovation, not radical innovation. Finally, Dan Saffer turns the discipline on its head.

Making Meaning

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GvYmBl0fttQ&w=500&h=350]

As researchers, designers, inventors, marketers–what we do is serve human beings. To truly serve people requires compassion and empathy for them as humans.

Rhea establishes the business value of design research by noting that of the three modes of business growth (mergers & acquisitions, operational efficiencies, organic), it is organic growth that is most highly valued by financial markets. Design drives innovation because organic growth requires new products and services to be developed.

The value that is created by design is determined by the customer, not the people building the product or service. Therefore, designers must have empathy and compassion for the end users of their products and services. Design research becomes “the skill of…identifying [and] facilitating the development and delivery of value.”

Exploring the ways in which design creates value, Rhea identifies several levels of value: economic (did you get a good deal for your money?), functional (was the product or service useful?), emotional (did you have a visceral response?), identity/status (does participating or using the product tell your peers something about yourself), meaningful (does the experience of the product reinforce the value of your life?). This final level is the apex of design achievement. If a product or service creates a meaningful experience, then it reinforces who we are as people.

Rhea gives the example of Patagonia, a brand whose values are so clear and congruent that for many outdoor enthusiasts, purchasing products equates to participation within a community of shared values. By creating a meaningful experience through authentic and clear brand values, the company provides its customers with a shared sense of value and alignment. This transcends functional usage–it is why Harley Davidson has such passionate customers. They are not just buying a product, they are participating in an experience which reinforces their personal values and self-images.

Design and design research can help locate the meanings that people assign to their lives and the world. Knowing this, designers can create meaningful experiences that reflect and reinforce the values that people have. Making the connection at the level of meaning is powerful because it aligns a company’s offering with the fundamental identities, beliefs, and values that people hold. This type of relationship goes far beyond an exchange of economic value or utility benefit.

The Research – Product Gap and Two Types of Innovation

Norman structures his talk around two themes: 1) the gap between researchers and product development teams; and 2) how design research contributes to incremental and radical innovation.

Norman says that no radical innovation has ever been the result of design research. None of the recent technology product innovations such as facebook, Twitter, Google, iPhone, Tivo, or foursquare was created after an exhaustive design research phase. He recalls that when Steve Jobs re-joined Apple, one of the first things he did was to fire the design research team along with the usability team. Norman asks: what resulted? Better designed products.

Technology First. Needs Last.

The rule is technologies do whatever they think is neat.

Norman notes that all radical innovations begin with a technological capability doing something “because it can.” There is not necessarily a need or customer in mind. A novel idea or capability is created because it is interesting or does something that was never possible before. Applications come next–sorting out how the technology can be applied to some basic problems. Finally, a needs analysis is performed to match the capability to existing problems. “Ideas first. Justifications Last.”

Who is the Audience for Design Research?

Product teams want to know how to implement it, not how it feels.

The audience for design research is product development teams. However, there are fundamental differences of approach and interests between the two communities.

Researchers are curious, deep, and engaged. They seek understanding and deliver stories, abstractions and generalizations. Their outputs are publications and conference talks.

In contrast, product development teams are practical, results-driven, and engaged. These teams want specifics and practical results. Their outputs are shippable products that are robust, reliable, and cost-effective.

Human centered design frequently uses ethnography, ideation, rapid prototyping, and tests as tools. Product design, engineering constraints, materials, construction, service and maintenance, sales and marketing, end of life, and supply chain issues are typically not addressed or included. Likewise, the cost and return, “and the fact that you may not make any money” are absent.

Dogma Abounds

Strong Beliefs. Little Evidence.

Design research does not address whether a product resulted and whether it was successful. Rather, it is evaluated by the quantity of ideas, cleverness, winning design competitions, and journal and conference publications. Norman says that we can evaluate design as art and leave it at that, or we can view design as applied social science in which case it serves the advancement of knowledge about people and their behaviors and needs. When thinking about design in the context of new products, “we need to do a better job.”

Radical Innovation and Incremental Innovation

To address the research-product gap Norman turns to Roberto Verganti’s book Design-Driven Innovation. Radical innovations such as the movement from mechanical watches to digital watches are purely technology driven. Likewise, the availability of inexpensive small GPS chips drove a large number of consumer applications.

Verganti points out that there is another dimension of innovation which is driven by changes in meaning. In the context of watches, swatch re-imagined watches as jewelry rather than as a tool. When the leaders in the video game industry were having a processor weapons race, Nintendo took technology advancements in cheap sensors and accelerometers and created a family-oriented entertainment system (the Wii). Similarly, Apple has lead the way in using computers for entertainment and social interaction rather than simply traditional applications.

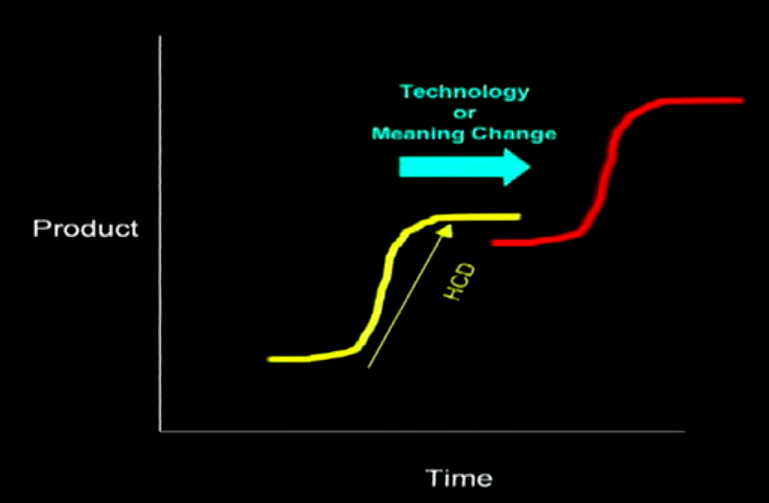

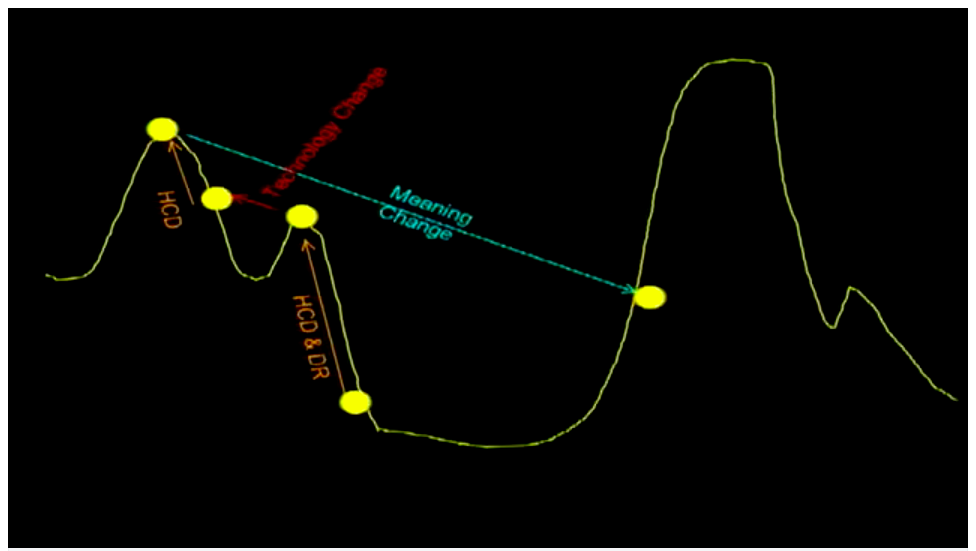

Norman takes the traditional traditional linked innovation S-curves (below) and shows that human-centered design and design research can help a product move incrementally to the next plateau, but it takes technology or meaning change to jump from one curve to another.

Norman depicts the flow of innovation (below) as starting with incremental innovation as a result of human-centered design and design research. This movement increases the utility and functionality of the product to a certain point. Then a technology change occurs and powers a radical innovation. Human-centered design then drives more incremental innovation again until a meaning change occurs and the innovation is thrown into a completely separate curve.

Another great example is minecraft. The game did not arise out of prolonged market research, ethnographic studies, and ideation. However, in late 2013, Lego began designing minecraft sets and launched a co-build project in which they evaluated and prototyped direct input from Lego enthusiasts. You can see Lego’s design research process here. Minecraft is an example of meaning change–the game introduced the ability to radically change the game environment and moved in the opposite direction of hyper-real high-defintion graphics.

Combining his findings with Verganti’s, Norman identifies three classes of innovation: incremental, technological, and meaning. Incremental innovation can be supported by human-centered design and conventional design research. Technological innovation is the domain of technologists and inventors (which could be anyone). Meaning innovation, as described in Verganti’s book, is where design-driven methods, primarily interactions with people outside the company who are generating the meanings in the marketplace, can be brought into play.

Translational Engineering

To address the research-product gap, Norman uses translational medicine as a model and proposes that design schools emphasize skills which would bridge the gap between research findings and practical applications. As the former VP of the Advanced Technology Group at Apple, he found that research outputs could not find a home in product development teams. The prototypes and ideas were not ready for market and could not be picked up by product teams and included in new offerings. He sees a need for a “third discipline” which can build the bridge and bring innovations to market–a great description of product management.

How to Lie with Design Research

Dan Saffer, who curates the Interaction Design Library, gives his take on success in Design Research in this presentation to the IIT 2007 Design Research Conference.