The roots of product management in industrial design

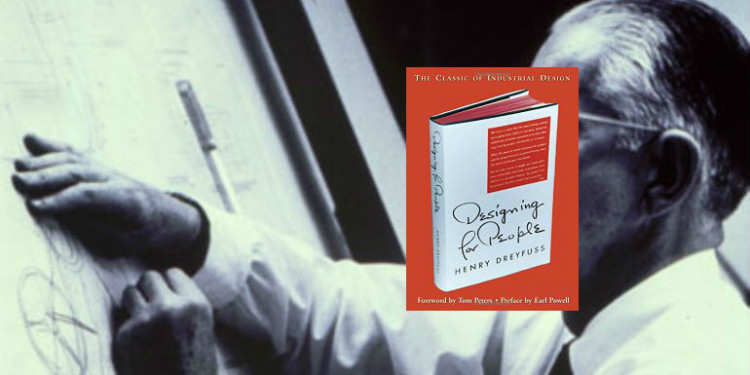

Designing for People by Henry Dreyfuss

Henry Dreyfuss wrote Designing for People

in 1955 when industrial design was emerging as a discipline distinct from art and engineering. Dreyfus was a leader in human-centered design (literally) through the development of detailed measurements of people for the purpose of designing better products. Much of his description of industrial design (emphasis on all aspects of a product with the user in mind) corresponds to what today’s product managers practice. He and his firm designed products, packaging, furniture arrangements, uniforms, and all aspects of the user journey. As a consultant, he presented full product designs to his clients, but always involved engineering, manufacturing, sales, and distribution. At the time, industrial design was emerging from the shadow of the art department and requests for last minute ornamentation of finished products.

Designing for people in a business context

What we are working on is going to be ridden in, sat upon, looked at, talked into, operated, or in some way used by people individually, or en masse.

Dreyfuss saw the value of what we call user experience today: “If the point of contact between the product and the people becomes a point of friction, then the industrial designer has failed. If, on the other hand, people are made safer, more comfortable, more eager to purchase, more efficient–or just plain happier–the designer has succeeded.”

He understood the value of study, research, and experimentation because “if the merchandise doesn’t sell, the designer has not accomplished his purpose.” Sales and market success were never far from his mind. He did not live in a vacuum of aesthetics. He and his team used “Joe and Josephine”, line drawings of a man and woman, to remind themselves of the end purpose of their designs and as tools for creating well fitting physical interfaces. Everything design they created was tested against these models of real people.

A multidisciplinary design process

…a successful performer in this new field [wears] many hats. He does more than merely design things. … He has an understanding of merchandising, how things are made, packed, distributed, and displayed. He accepts the responsibility of his position as liaison linking management, engineering, and the consumer and co-operates with all three.

Dreyfuss always evaluated client projects for feasibility. If a designer can’t add value or make a difference, the job should not be accepted. The first meetings are scheduled with engineering, production, advertising, sales, and distribution departments to understand their needs and constraints. From the outset, Dreyfuss involves all stakeholders and identifying limitations and, as a result, issues and risks.

Like a product manager, he asks:

what price bracket will the product fit into?

what new ideas are under development?

what means of fabrication are available and what new materials can be considered?

what is the proper timing of the product from a sales perspective?

how soon will the production department need the new design to meet the deadline?

what are the shipping methods and timelines?

what features are most desirable for advertising and marketing purposes?

Next, competitive analysis is performed and photographs of competitive products are placed on a board. The client’s product is used extensively by the designers.

The designers visit the factory to gain a deep understanding of the manufacturing methods available so that they do not propose a product and materials which are costly or cannot be effectively built.

The diagrams of measured humans are brought into the process to focus interchange of ideas between the designers and engineers. Prototypes and models are created and eventually presented to the client with the goal of a working prototype. Throughout the process “we constantly remind ourselves that competitors, too, may have been working on improved new designs that will hit the market simultaneously with ours.”

If the product is to be packaged, the design team also designs the container, carton, and price tag. Dreyfuss notes “occasionally we have designed the truck that delivers it.” This sounds much like the present day customer experience supply chain that Apple maintains to control all elements of its product. Dreyfus discusses the implications of packaging as ultimate storage for the product and how the product is displayed. He was keenly aware of the “unboxing” experience that is the hallmark of many products today.

Even in the years Dreyfuss was designing products, he found that “the realm of technical knowledge has become so vast and changes occur so rapidly that no one can digest it all. So the industrial designer consults others frankly and openly.”

Survival Form

We deliberately incorporate into the product some remembered detail that will recall to the suers a similar article put to a similar use. People will more readily accept something new…if they recognize in it something out of the past.

Dreyfuss gives several examples of new products which contain hints of previous products–decorations which remind one of a previous generations household objects or a visual feature that creates a bridge between a new device and it’s predecessor. He notes that although numbers on a clock are completely superfluous, clocks without them do not sell very well. Although the concept of a survival form goes against the grain of design purity, Dreyfus, with his feet always firmly planted on the ground, says: “ours is the ever changing battle-ground of the department store rather than the Elysian fields of the museum.” He visited retail stores as frequently as possible and even joined customer repair teams in order to understand his end customers and how the product performed in the real world.

Looking into the future

An eternal problem for product development is time to market. For a designer, “If his design is too static, the product will be out of date and old-fashioned against competition. If he goes too far, the public may consider it extreme and reject it.” Dreyfuss grounds his judgements in knowledge of merchandising, distribution, consumer trends, new manufacturing methods, and price sensitivity–all research that a product manager must perform as new products and upgrades are being considered.

Dreyfuss captures the key elements of industrial design that correspond to what is today the domain of product management. Other than references to 1950’s products, the books reads as if it were written today. Dreyfuss highlights aspects of product development that are still practiced by industry leading companies like Apple.