The race to sameness

As product categories mature, there is a tendency for all offerings to resemble one another. Traditional marketing techniques and competitive pressure result in a homogenous set of products. To break free of this cycle, companies must invest in their differences rather than attempting to match competitor’s strengths.

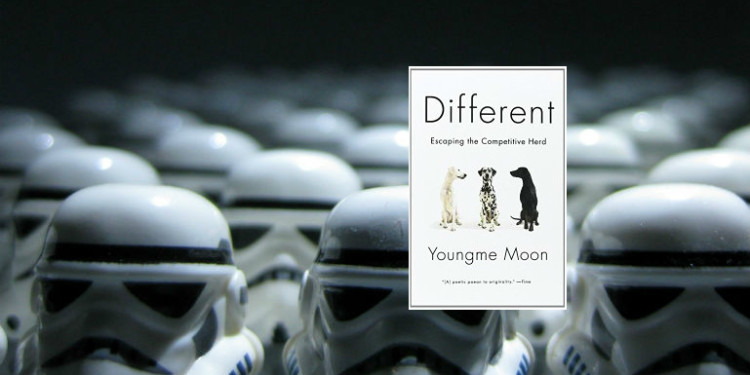

Different: Escaping the Competitive Herd

by Youngme Moon

Although many business books have been written about differentiation in the market (“differentiate or die!”), Moon’s book is different because she offers insights into why being different works rather than providing a formula for how to differentiate. She makes many observations about difference from various perspectives and adopts a humanistic stance towards the topic. Moon cites many popular business case studies such as Ikea, Harley Davidson, and Jet Blue, but provides a more psychologically oriented framework for considering these brands than is present in most popular marketing books.

Although differentiation is the basis of competitiveness in the market, Moon points out that categories frequently get to the point where consumers are disbelieving of differences between brands and products. Product categories like detergent, cereal, and bottled water have reached a level of micro-segmentation which becomes overwhelming for consumers.

The marketer needs to be able to ascertain the dimensions of our desire–paying heed to the things we want…but paying equal heed to the things that we do not.

Heterogenous homogeneity

Try explaining to a foreigner the difference between Crest and Colgate. Try explaining the difference between a Honda and Toyota.

Moon begins the book by asking the reader to imagine standing in the cereal aisle of a supermarket with a goal of selecting a new cereal. To do this, you must divide the cereal types into health/not healthy, adult/kid, sweet/plain and other categories. This market segmentation requires you to be an expert in the category, knowledgeable in the many sub-segments of cereal types. To people who are not intimately familiar with the nuances of features and functions of product types, market categories can be incomprehensible. As Moon puts it, “where a connoisseur sees the differences, a novice sees similarities.”

As market segments become mature, the initial differences between products disappear as all participants micro-segment and competition drives development of parity features and attributes. It’s a bit like Clayton Christensen’s theory of disruption–as businesses adhere to best practices they can sow the seeds of their own undoing. In this case, hyper-mature categories suffer from a sameness borne of relentless

as the number of products within a category multiplies, the differences between them start to become increasingly trivial

Shoring up weak points

Moon gives the example of Jeep and Nissan. Originally, Jeep was known primarily for its ruggedness and Nissan for its reliability. Over time, both brands have moved toward a blended set of attributes and now Jeep is still primarily rugged but also has a lot of reliability while Nissan has built up its rugged aspect to nearly match its reliability. Brands attempt to amplify all available attributes rather than focusing on their unique strengths. For Moon, Jeep should have doubled-down on ruggedness to distance itself from Nissan. As brands seek to equalize all features and functions, consumers can’t tell the difference between a comfortable Hummer and a 4 wheel drive Lexus. Categories become homogenized through this conformity and convergence.

Products are no longer competing against each other; they are collapsing into each other in the minds of anyone who consumes them

Businesses have a hard time breaking free from this pattern because traditional marketing techniques are aimed at finding competitive gaps and filling them. The race towards parity from all participants results in an undifferentiated mass of features and attributes. This slicing-and-dicing of the category is an attempt to micro-segment and find another elusive pocket of like-minded consumers. By adopting this approach, brands effectively erase the differences within the category.

a telltale sign that a category has achieved hyper-maturity: Overall growth has slowed to a trickle even as the competitive hyper-activity in the category has become more frenzied than ever

Augmentation strategies

Brands use of two strategies to keep pace with their competitors: augmentation-by-addition and augmentation-by-multiplication. In augmentation-by-addition, new features are added to products, resulting in “additional features”, “new and improved”, “better than ever!”, and “now, with even more features!” Augmentation-by-multiplication adds new varieties of products: regular, diet, sugar free, zero calorie, cherry, acai berry, and gluten free varieties.

As each brand identifies a new attribute to invest in and release to market, competitors immediately invest in parity and the playing field is level. When new features are added, consumers become habituated to the current set of benefits and this initiates another frenzied augmentation project. As consumer satisfaction is recalibrated, companies have no other choice than to initiate the cycle again. The tide of consumer satisfaction rises until a point where augmentation reaches a point of diminishing returns.

Consumer coping mechanisms

It’s easy to be a Haagen-Dazs loyalist when Haagen-Dazs is the only major player in the premium ice cream game; when the market is packed with premium clones, Haagen-Dazs loyalists are by definition going to be harder to find.

Faced with this blur of products features and attributes, consumers adopt one of several coping strategies. Overall, they tend to evaluate a category as a whole rather than the individual brands within it. Towards the category itself, consumers may be loyal, pragmatic, reluctant, or opportunistic. Although brand marketers are seeking to build brand loyalty, the result is that consumers paint the entire category with a broad brush. Additional improvements no longer add value. Given how important consumption is to our identities, brand loyalty remains elusive as consumers define themselves by a wide variety of relationships to product categories.

Moon calls this overall phenomenon “jumping the shark“–the point at which a brand loses relevance through the introduction of one too many features which do not resonate with consumers. Through an unrelenting pursuit of sameness, brands achieve an undesirable level of indifference in the minds of consumers and all brands within a category a lumped together. Each of us is a loyalist to one brand, a pragmatic with respect to another, and reluctant elsewhere.